This webpage is entirely devoted to

Belgian Lambic, Geuze, Faro and other Lambic-derived beers.

This webpage is entirely devoted to

Belgian Lambic, Geuze, Faro and other Lambic-derived beers.

This Belgian beer-style goes back to a long tradition, and has made a revival in recent years. Because I like a delicious Geuze or "Brussels Champagne", I created this webpage dedicated to this unique Belgian beer-style which is the result of spontaneous fermentation.

History

The Lambic style can trace its roots back over 400 years, and has remained mostly unchanged from its introduction. The first written recipe is dated 1516 and accounts from 1559 mention the

production of Lambic "according to an old recipe".

In fact in ancient Mesopotamia a beer that could be thought of as the "roots" of Lambic was brewed by the Sumerians, about 5500 BC. Sikaru, the premium beer of the day, was brewed from

60% malt, 40% raw wheat, used wild fermentation and was flavored with herbs like aniseed and cinnamon.

Although it is impossible to confirm the origin of the word "Lambic" ("lambiek" in Flemish / Dutch), it is most likely a distortion of Lembeek (Flemish) or Lembecq (French),

a present and historic Lambic brewing town. Other sources relate it to "alambic" or to "lambere" (Latin).

Brewing of Lambic

The oddities of the style are many. Like its ancient Mesopotamian predecessor, the

wort is composed of 60-70% barley

malt and 30 - 40% unmalted wheat.

The hops are aged to curtail the introduction of hop character. These aged hops have lost their bittering power but have retained their antiseptic properties.

The brewing method of Lambic is the turbid mash method or "slijmmethode" in Flemish with the peculiarity that the brewer intends to

obtain a highly dextrinous wort, more appropriate for

sustaining a long fermentation by a mixed flora of microorganisms and leading to the typical Lambic flavor.

The most typical differences between the brewing process of a conventional lager beer and Lambic are the following:

- To brew a spontaneous fermented Lambic, no yeast is artificial added to the wort, but the wort is exposed to the open air of the "Zennevalei" (E: Senne-valley).

The result of this method is that wild yeast cells, among them Bretanomyces bruxellensis and B. lambicus, which are always in the open air in the environment of Brussels,

come into the wort and start on a natural, spontaneous way the fermentation.

- To brew a spontaneous fermented Lambic, no yeast is artificial added to the wort, but the wort is exposed to the open air of the "Zennevalei" (E: Senne-valley).

The result of this method is that wild yeast cells, among them Bretanomyces bruxellensis and B. lambicus, which are always in the open air in the environment of Brussels,

come into the wort and start on a natural, spontaneous way the fermentation.

- More than 30 percent unmalted wheat is utilized, this in contrast to lager beers, where corn or rice is used.

- The Lambic brewer uses old dry hop, aged three years. He does not want the bitterness of the fresh hop, but the conservation property of the dried hop.

The lager brewer uses young hop which gives beer its typical bitter taste.

By law the brewer must use min. 30 % unmalted wheat and 70% malt (1/3 winter; 2/3 summer cereal) and a wort-strength of 11-12 degrees Plato, which indicates the ratio of fermentable sugars to water in the beer. The acidity of the Lambic should be min. 30 milli. equivalents NaOH and the volatile acidity: min. 2 milli. eq. NaOH. The spontaneous inoculation from open coolship is a requisite to create a Lambic.

Due to the spontaneous fermentation, Lambic is a seasonal beer, which can be brewn only in the winter season (October-May). In summertime, there are too much

undesirable bacteria, which can infect the wort and influence negatively the fermentation.

The very old brewing procedure of Lambic goes as follows (the precise procedure may vary between different breweries):

1. A batter (mash - see picture) of water, malt and at least 30 % wheat is made at 45 degrees Celsius.

At this temperature the malt releases his first soluble elements, under which the most important: starch.

2. The second step is to warm up this brew to 52 degrees Celsius. By this, the proteases break off the malt flour, through which the brewer obtains an optimal solution of proteins.

This white turbid extract is called "the milk" or "the slime"

3. By increasing the temperature of the slime to 65-75 degrees, the enzymatical conversion of starch into sugar is taking place.

4. After filtration of this solution, the brewer obtains an extract of sugars, proteins and minerals, which is called "the wort". this extract is seasoned by dried (aged) hops (600 g/l) and boiled for 4 hours.

5. Further, the boiled wort goes into the "koelbak" (Flemish) or "bac refroidissoir"(French), an open, shallow cooling tun, made of copper and located in a well ventilated room, to cool down overnight.

It is at this crucial moment that the inoculation takes place: specific wild yeasts and enteric bacteria, altogether a mixture of 86 microorganisms, which are floating in the air around Brussels,

fall down into the wort. The resulting process is called spontaneous fermentation and this mystery of the Lambic-beers is unique in the beer-world.

6. Next day, the inoculated wort is pumped into old oaken or chestnut barrels, called "tonnen" (Flemish) or "tonneaux" (French, 250 liters) "pijpen" or "pipes"(650 liters)

or "foeders" or "foudres" (3000 liters) where the fermentation can start. The micro-environment of these barrels contributes to the specific flavor of the Lambic.

The brewers use old barrels because the wood has lost its tannin, which would affect the flavor of the Lambic. These old barrels mainly come from the Porto or Sherry region.

The evolution of the Lambic goes slower in the larger barrels, but it is said to be better. Nowadays brewers are also using steel tanks with wood chips for the fermentation of Lambic.

After a few days, depending on the weather, the fermentation starts. White foam appears on the upper hole of the barrel. Later, the foam becomes brown and form a natural stopper,

which preserves the beer for external factors, like undesirable bacteria and oxygen, but the CO2 (carbon dioxide), released by fermentation, can escape.

The principle fermentation is passing on to a second fermentation and further to a cascade of other smaller fermentations and finally there is the maturation of Lambic,

which takes up to 2 years. Lambic requires several years to come of age, during which time, dust and cobwebs cover the barrels.

The production of Lambic is limited to the cooler seasons, as during summer other micro-organisms may interfere with the natural fermentation .The production of Lambic

is usually confined from mid-October to May (15 October to 15 May), allowing for the wild yeast and beer to ferment during the summer.

Microorganisms involved in the spontaneous fermentation of Lambic

The purely wild yeasts that enter the mash and perform the fermentation, give the Lambic an untamed (and sometimes unpredictable) taste not possible using cultured yeasts.

The spontaneous fermentation by enterobacteria and Brettanomyces spp., altogether some 86 different micro-organisms, followed by the maturation in old oak barrels gives these beers their unique taste and flavor.

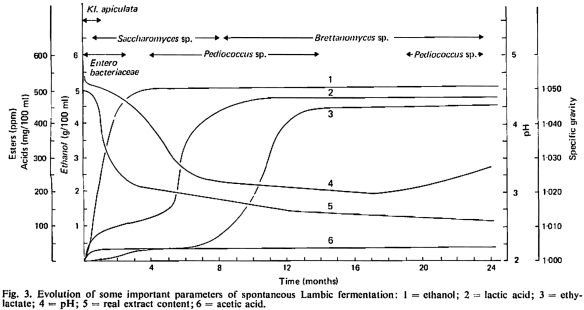

The fermentation process

Microbiological aspects of spontaneous wort fermentation in the production of lambic and gueuze, van Oevelen et al, 1977

Three to seven days after the wort has been cooled, the primary fermentation starts with the development of Kloeckera apiculata

(Hanseniaspora uvarum) yeasts together with wort

enterobacteria,

which produce large amounts of acetic acid

(mixed-acid fermentation).

The enteric bacteria persist only for about one month because of pH lowering and ethanol production.

After two to three weeks yeasts of the Saccharomyces family take over like S, cerevisiae, S. bayanus, S. globosus, S. dairensis and S. uvarum and completes the main or

primary alcoholic fermentation in three to four months. After this a strong bacterial activity takes place of strains of lactic acid bacteria

Pediococcus mainly P. damnosus and Lactobacillus, for 3 to 4 months.

Pediococcus damnosus and

Pediococcus cerevisiae

are responsible for some of the intense lactic sourness present in Lambic. The production of

lactic acid by these bacteria,

causes a strong drop in the pH of the wort. At this stage of the fermentation, the Lambic is often ropy or oily. This phenomenon is caused by the production of slime by P. damnosus

from the glucose or maltose in the wort. At this stage the Lambic is said to be sick. This slime, which consists of carbohydrates, nucleic acids and proteins, is later hydrolyzed by

Brettanomyces spp..

After five to eight months, Brettanomyces species appear in the wort. They further reduce the residual extract and are to a large part responsible for the unique flavor of Lambic.

Two of the Brettanomyces species involved in Lambic production are Brettanomyces lambicus and Brettanomyces bruxellensis. They are able to ferment dextrins, which the Saccharomyces was unable to metabolize.

There are more differences between Saccharomyces and Brettanomyces, that account for the typical flavor of Lambicbeers.

Brettanomyces lambicus is an important contributor to the flavor profile of Lambic beers and contributes a unique and complex flavor sometimes described as "horsey" or "old leather",

caused by tetrahydropyridines. Brettanomyces bruxellensis produces an odd horse-like aroma and flavor. The Brettanomyces spp. produce very little carbon dioxide, in contrast to S. cerevisiae.

Brettanomyces contributes to the character of the Lambic by means of the secondary fermentation products of the fermentation pathway, like ethyl lactate and ethyl acetate (esters),

due to a high esterase activity. Brettanomyces lambicus is a slow growing yeast which takes several weeks to ferment and develop its unique character.

Brettanomyces lambicus is dominant in the countryside surrounding Brussels as opposed to Brettanomyces bruxellensis which is dominant in the city of Brussels.

Other yeasts which are also detected in Lambic are yeasts of the genera Candida, Hansenula and

Pichia. They contribute to the fruity character of Lambic.

It takes about two to three years for the entire process to complete and to produce a mature Lambic. Tasting Lambics of different stages of fermentation is an exciting experience,

as the flavor changes through the process.

By blending young and old Lambic to obtain Geuze, the secondary fermentation starts in the bottle.

It is important to keep in mind that all these microorganisms, in order to create a Lambic, must work in a specific sequence. Each microrganism depends on the metabolisation products of its predecessors,

to create the unique Lambic flavor.

Geographic location of Lambic-style beers

Due to the limited environment in which these micro-organisms grow, the traditional Lambic beers can only be produced in a small region of Belgium (Europe), surrounding the Belgian (European) capital Brussels,

in the valley of the river Zenne (E: Senne),

which flows through a region called the Pajottenland

in the south-western part of the province Flemish Brabant (Vlaams-Brabant) and

Walloon Brabant (Brabant wallon).

Traditionally, Lambic is brewed mostly within ten miles of the city of Brussels. Nowadays, the production is concentrated in the western part of Brussels and in the nearby "Pajottenland".

There are a few breweries outside the Pajottenland, which also make a beer of spontaneous fermentation, they are located in West-Vlaanderen. This beer however is not a real Lambic.

Only when the inoculation with micro organisms takes place in the traditional region, you may get a real Lambic.

Legislation

A Belgian Royal Decree of 20 May 1965 concerning the usage of names for beer (published in the Belgisch Staatsblad / Moniteur Belge on June 1965, pp. 7219-7220) restricts usage of

the names lambic(French),lambik(Flemish),

gueuze(Fr.),geuze(Fl.),

gueuze lambic(Fr.),geuze lambik(Fl.),

to beers of spontaneous fermentation. They have to contain at least 30 percent wheat and the

original density of the wort has to be at least 5 degrees.

A Belgian Royal Decree of 17 July 1973 concerning the usage of names for beer (published in the Belgisch Staatsblad / Moniteur Belge on 18 April 1974, p. 9940) restricts the usage

of these names to beers produced by inoculation from the air, by cooling of the wort in an open cooler.

A Royal Decree of 29 March 1974 concerning beer(published in the Belgisch Staatsblad / Moniteur Belge on 4 September 1973, pp. 5490-5493) defines in article 1.2.a even more precise

that these beer types are restricted to beer of spontaneous fermentation, with a density of at least 11 degrees Plato and a minimum acidity (min. 30 milli-equivalents NaOH and a volatile acidity of

min. 2 milli-equivalents NaOH). At least 30 percent wheat should be used for the production.

Since this Royal Decree the Flemish names have been changed to the French spelling in article 4.1.b. .

A Belgian Royal Decree of 31 March 1993 concerning beer (published in the Belgisch Staatsblad / Moniteur Belge on 4 June 1993, pp. 13507-13509) replaces the Royal Decrees of 1965,

1973 and 1974. For the beers of spontaneous fermentation it defines the same rules as the Royal Decree of 1974, but now not all of the beer must be derived from spontaneous fermentation.

A regulation of the European Community of 21 January 1997 according to the regulation (EEC) No. 2082/92 on certificates of specific character for agricultural products

and foodstuffs ( GREEN EUROPE. No. 1. 1996. Office for Official Publications of the EC. Luxembourg. 45 p. Tabl. Graph. Ann. Free. ). This European regulation defines new rules for the the

lambic beers, the new rules give a better protection of the traditional product. European legislation however protects products based on the traditional production methods or region,

not both together. A traditionally produced Geuze will now be called "Old" Geuze.

I just give you the names of the traditional products, as they will be used once the new legislation is incorporated in the national law:

For Geuze it will be:

vieille gueuze, vieille gueuze lambic, and vieux lambic(Fr.),

Oude Geuze, Oude Kriek Geuze-Lambiek and Oude Lambiek(Fl.).

For fuit beers derived from Lambic:

vieille kriek, vieille kriek lambic, vieille framboise lambic and vieux fruit lambic(Fr.),

Oude Kriek, Oude Krieklambiek, Oude Frambozenlambiek and Oude Fruitlambiek(Fl.).

For Faro, the name is written the same in French and Dutch/Flemish.

The beers that do not have "vieille" or "Oude" in their name will be the more commercial and mostly sweetened mass-market products.

Beer types

Lambic - Lambiek

Lambic (French) or Lambiek (Flemish) is a very ancient beerstyle, unblended Lambic has a rich flavor, quite different from other beers nowadays. Nowadays, Lambic on draught is hard to find.

Only in a few pubs in and around Brussels you still can taste the curious sherry-like flavored beer. It lacks the carbon dioxide and has a more sour taste than modern day beers.

The traditional Lambic is a sour beer of 100% spontaneous fermentation with at least 30% of wheat used as a basic ingredient. Young Lambics ("platte", "joenk", "vos") are dry, sour,

cloudy and similar in taste to cider. Aged Lambics are more mellow and settled. Young Lambic, or "vos" (Flemish) (E: fox) Lambic, is slightly sour, old Lambic has greater acidity.

Some Lambic is sold as such, but most Lambic is used to produce Geuze.

O.G.: 1.040 - 1.056; Alcohol: 4 - 6%; IBU's

(international bittering unit): 3 - 22;

SRM: 4 - 13.

Geuze - Gueuze

Geuze is made of 100% Lambic beer which undergoes additional fermentation on the bottle. Geuze was created in the 19th century in Lembeeq. The blending of old and young pure

Lambic is the traditional way to make Geuze. The skill in producing a good Geuze is in balancing the right young and old Lambics in the right quantities. The right ratio young/old is

depending on the maturation degree (end attenuation) of each of them.

Once the blend is bottled, it undergoes a secondary fermentation in the bottle (Method Champenoise), creating the unique flavor. After 6 months the Geuze obtains a golden color and a cidery,

winey palate; reminiscent, perhaps, of dry vermouth with a more complex and natural flavor.

Geuzes tend to be sweeter than Lambics, and are always livelier, causing them to be dubbed the "Champagnes" of the beer world. The right flavor and amount of carbon dioxide is caused by

the secondary fermentation in the bottle, for which it takes at least a year in the bottle to make a good geuze. The taste of Geuze ranges from sour over sourish-bitterish to bitterish. A traditional, unsweetened, Geuze contains only about 0.2 % sugar containing substances. An old traditional, unsweetened, Geuze is therefore well tolerated by diabetics, due to its very low sugar content. Geuze is golden to light amber in color.

Geuze is the traditional beer for carbonade flamande, as well as a delicious beverage with seafood or other salty meals. It is also delicious with cream sauces.

Beside the traditional unsweetened Geuze, there is also a more commercial Geuze that dominates the market. It is pasteurized and has a sweeter taste.

O.G.: 1.040 - 1.056; Alcohol: 4 - 6%;

IBU's (international bittering unit): 3 - 23;

SRM (Standard Reference Method): 4 - 13.

Faro

Nowadays faro is made from spontaneous fermentation Lambic (from moderate gravity wort) to which is added burnt sugar or candy sugar (chaptalized), so that it gets

a sour-sweetish taste. Faro has a low alcohol level.

Traditionally, Faro was made by blending Lambics produced from high- and low-gravity worts. A lump of sugar was added to the glass to sweeten the Faro. This was probably

the beer being served in Breughel the Elder his paintings of Flemish Village Life.

O.G.: 1.040 - 1.056; Alcohol: 4 - 6%; IBU's: 3 - 22; SRM: 4 - 13.

Mars beer

Mars beer was made from the late, low-gravity worts, it was mainly produced for home-use. Today mars beer is no longer commercially available.

Fruitbeer

Lambics are sometimes casked with cherries, raspberries, or other fruit to produce fruitbeer. A fruitbeer can vary as to whether it is of low fermentation, spontaneous fermentation (Lambic) or high fermentation. The only thing one does is add real cherries or raspberries or the cheaper essences, juices or syrups. Thus one gets Flemish brown "kriek" beers (E: cherry) or geuze "kriek" beers. Besides the traditional cherry or "frambozen" (E:raspberry) beers other fruit beers are all beers on the basis of essences, juices or syrups - no real fruit is involved.

Kriek: orangey to deep red in color, combines the character of geuze with fresh fruit and pit aromas and some residual sweetness, it has a delicious taste of sparkling cherry champagne.In origin, this sweet-acid drink was obtained by adding fresh black cherries to a barrel Lambic of 6 months young. The addition of fruits provokes a new fermentation in the oak barrels. After another 8 to 12 months, only peels and stones left and the Kriek-Lambic is ready to be filtered and bottled.

O.G.: 1.040 - 1.072; Alcohol: 4 - 7%; IBU's: 3 - 22; SRM (Standard Reference Method): red.

Framboise: ruby red with huge raspberry aroma. It is just delicious with chocolate cake.

O.G.: 1.040 - 1.072; Alcohol: 4 - 7%; IBU's: 3 - 22; SRM: red.

Peche: made with peaches. It is not tot be despised with pancakes, filled with ice-cream.

O.G.: 1.040 - 1.072; Alcohol: 4 - 7%; IBU's: 3 - 22; SRM: 4 - 15.

Cassis: made with black currents. Very aromatic and rich.

O.G.: 1.040 - 1.072; Alcohol: 4 - 7%; IBU's: 3 - 22; SRM: 4 - 15.

Lambic breweries and geuze blenders

This list provides an overview on the remaining tradtional lambic breweries and gueuze blenders. Besides traditional ('oude' or 'vieille') gueuze, some of them also produce more commercial (mass market) products.

- 3 Fonteinen - brewery

- Boon brewery

- De Cam

- Cantillon with Brussels Gueuze Museum and a public brewing session once a year

- De Troch

- Girardin

- Hanssens

- Den Herberg

- Lambiek Fabriek

- Lindemans

- Mort Subite

- Oud Beersel

- Tilquin

- Timmermans

Enjoying gueuze and information

Finding a good restaurant or pub where they serve a decent traditional 'oude' or 'vieille' (old) gueuze should be easy in Belgium. The list of traditional breweries and blenders should provide a guide of what you should be looking for. You should always ask for a 'oude' or 'vieille' gueuze in order to avoid the mass market non-traditional beers.

- High Council for Artisanal Lambic beers - HORAL

- Lambic Academy by HORAL

- Toer de Geuze by HORAL - biannual event since 19 October 1997

- De Lambiek, visitor center

- Geuzeroute by bike

- Lambiekstoempers vzw and Agenda

- The Gueuze Society - The Day of the Kriek - The Day of the Lambic

- Restaurant 3 Fonteinen - restaurant (Beersel, Belgium)

- De Heeren van Liedekercke - restaurant (Denderleeuw, Belgium)

- Verzekering tegen de Grote Dorst - pub and shop (Eizeringen, Belgium)

- A La Bécasse - restaurant (Brussels, Belgium)

- Chez Moeder Lambic - pub (Sint-Gillis, Brussels, Belgium)

- A La Mort Subite - pub (Brussels, Belgium)

- Café Kulminator - pub (Antwerp, Belgium)

- Café 't Brugs Beertje - pub (Brugge, Belgium)

- Den Herberg - pub (Buizingen, Belgium)

- De Trollekelder - pub (Gent, Belgium)

- In den Spytighen Duvel - pub (Turnhout, Belgium)

- Lambic - Beer report

- Gueuze - Wikipedia

- Lambic - Wikipedia

- How to Drink Lambic Beer

- Geuze info (Dutch

- Gueuze - Zythos (Dutch)

- Zythos (Dutch)

Books

Het mysterie van de geuze

Jos Cels

Roularta-Books, 1993, 144 pp.Classic Beerstyle Series nr. 3, Lambic

Jean-Xavier Guinard

Brewers Publications, a division of the Association of Brewers, 1990, 159 pp.Geuze en humanisme

Hubert van Herreweghen

Brussel, Vlaamse Club, 1955, 40 pp.Les memoires de Jef Lambic

Unknown

Editions La Technique Belge, 19th Century, 114 pp.De Grote Belgische Bieren (original title: The Great Beers of Belgium)

Michael Jackson

Media Marketing Communications N.V. (Belgium), 1997, 343 pp.

Publications in Journals

Synthesis of aroma compounds by wort enterobacteria during the first stage of lambic fermentation.

E. Dawoud, H. Verachtert

J. Inst. Brew. 98, pp. 421-425Brettanomyces I. Occurrence, characterisitcs and effects on beer flavour

R. B. Gilliland

J. Inst. Brew. 67, pp. 257-261Metabolism of volatile phenolic compounds from hydroxycinnamic acids by Brttanomyces yeast.

T. Heresztyn

Arch. Microbiol. 146, pp.96-98Yeasts in mixed culture with emphasis on lambic beer brewing.

H. Verachtert, Shanta Kumara, E. Dawoud

In Yeast: biotechnology, and Bioengineering, eds Verachtert and De Mot

pp. 429-473Interactions between Enterobacteriaceae and S. cervisiae.

H. Verachtert,E. Dawoud, Shanta Kumara

YEAST 5 Spec. Issue pp. 67-72Identification of lambic superattenuating micro-organisms by the use of selective antibiotics.

Shanta Kumara, H. Verachtert

J. Inst. Brew. 97, 181-185Wort enterobacteria and other microbial populations involved during the first stage of lambic fermentation.

H. Martens, E. Dwoud, H. Verachtert

J. Inst. Brew. 97, pp. 435-439Belgian lambics

G. Noonan

Zymurgy, 10, pp. 26-29Fatty acids and esters produced during the spontaneous fermentation of lambic and gueuze

M. Spaepen, D. Van Oevelen, H. Verachtert

J. Inst. Brew., 84, pp. 278-285 (1978)Esterase Activity in the genus Brettanomyces

M. Spaepen, H. Verachtert

J. Inst. Brew., 88, pp. 11-17 (1982)Higher fatty acid (HFA) and HFA-ester content of spontaneously fermented Belgian beers and evaluation of their analytical determination.

Marijke Spaepen, D. Van Oevelen, H. Verachtert

Brauwissenschaft, 32, pp. 1-6 (1979)Enkele nieuwe resultaten van het microbiologisch en biochemisch onderzoek van gueuze.

Marijke Spaepen, D. Moens, J. Heyrman, H. Verachtert

Cerevisia, 6, pp. 23-27 (1981)Microbiology and Biochemistry of the natural wort fermentation in the production of lambic and gueuze.

D. Van Oevelen

Agricultura (Heverlee),26(4), pp. 353-505Slime production by brewery strains of Pediococcus cervisiae

D. Van Oevelen, H. Verachtert

J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem., 27, pp. 34-37 (1979)Synthesis of aroma components during the spontaneous fermentation of lambic and gueuze

D. Van Oevelen, F. de l'Escaille, H. Verachtert

J. Inst. Brew., 82, pp. 322-326 (1976)Microbiological aspects of spontaneous wort fermentation in the production of lambic and gueuze

D. Van Oevelen, M. Spaepen, P. Timmermans, L. Geens, H. Verachtert

J. Inst. Brew., 83, pp. 356-360 (1977)Origin and evolution of dimethyl sulfide and vicinal diketones during the spontaneous fermentation of lambic and gueuze.

D. Van Oevelen, P. Timermans, L. Geens, H. Verachtert.

Cerevisia, 3, pp. 59-66 (1978)La fermentation spontanee de la gueuze

H. Verachtert

Cerevisia, 8, pp. 41-48 (1983)Lambic and gueuze brewing: mixed cultures in action

H. Verachtert

Foundation Biotechnical and Industrial Fermentation research, Vol. 7 Finland pp. 243-263.Identification of lambic superattenuating micro-organisms by the use of selective antibiotics.

H.M.C. Shantha Kumara, H. Verachtert

J. Inst.Brew., 1991, pp. 181-185

PhD Theses

Characteristics of Enterobacteriaceae involved in lambic brewing.

Ensaf Dawoud

PhD Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit te Leuven, February 1987Microbiology and biochemistry of lambic beer overattenuation.

H.M. Chandana Shantha Kumara

PhD Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit te Leuven, November 1990Dextrinases from lambic organisms: Brettanomyces lambicus and Lactobacillus brevis isolation and characterization.

Frank Maris

PhD Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit te Leuven, 1990Bijdrage tot de biochemie en mikrobiologie van Lambic en Gueuze.

Marijke Spaepen

PhD Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit te Leuven, 1982Bepaling van het aminozuurverloop tijdens het produktieproces van lambic en gueuze met de automatische aminozuuranalysator.

K. Mulders

PhD Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit te Leuven, 1982Microbiology and biochemistry of the natural wort fermentation in the production of Lambic and gueuze.

Dirk Van Oevelen

PhD Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit te Leuven, 1979

Copyright notice and disclaimer

The information contained in this website is for general information purposes only.

The information is provided by me in good faith and while I endeavor to keep the information up to date and correct,

I make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness,

accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information,

products, services, or related graphics contained on the website for any purpose.

Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

Any information on this website is provided in good faith but no warranty can be

made for its accuracy. As this is a work in progress, it is still incomplete

and even inaccurate. Although care has been taken in preparing the information

contained in my webpages, I do not and cannot guarantee the accuracy thereof.

Anyone using the information does so at their own risk and shall be deemed

to indemnify me from any and all injury or damage arising from such use.

In no event shall I be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this website.

Through this website you are able to link to other websites which are not under the my control. I have no control over the nature, content and availability of those sites. The inclusion of any links does not necessarily imply a recommendation or endorse the views expressed within them.

Every effort is made to keep the website up and running smoothly. However, I take no responsibility for, and will not be liable for, the website being temporarily unavailable due to technical issues beyond my control.

These webpages of course represent only personal interests, opinions and ideas and

were created without a commercial goal. You may download, display, print and copy, any material at this website,

in unaltered form only, for your personal use or for non-commercial use within

your organisation.

Should these webpages or portions of these webpages be used on any Internet

or World Wide Web page or informational presentation, that a link back to

this website

(and where appropriate back to the source document) be established. Send

a short notice by email when you copy these webpages, or part of it

for your own use.

To the best of my knowledge, all graphics, text and other presentations

not created by me on my webpages are in the public domain and freely available

from various sources on the Internet or elsewhere and/or kindly provided

by the owner.

If you notice something incorrect or have any questions, feel free to send me an email.

The author of this Webpage is Peter Van Osta. Back to my homepage.

Email: pvosta{at}gmail{dot}com