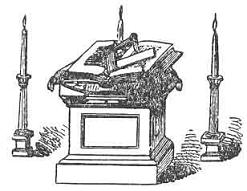

The Constitutions of the Freemasons by James Anderson, 1723 edition

Freemasonry is a curious phenomenon. It is also one of the best known fraternal organisations and a lot of information is available on freemasonry. It can be seen as practical philosophy or a living encyclopaedia of religious, philosophical and historical myths and legends. As such it is interesting to use it as a framework to study some philosophical principles. The self-declared principal idea of Freemasonry as a fraternal organisation is to take a good man and make him a better man by developing his morality. Although legend has it that it was founded at the building of Solomon's temple, it is known that during the building of cathedrals in the 1200's, the stoneworkers of the British Isles and Western Europe were organized into guilds which had the usual three degrees of master, journeyman, and apprentice. The beginning of the modern Masonic Order dates from the year 1717 when the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster was founded.

Studying freemasonry as a layperson seems to pose some challenges, but at least it will be fun and interesting. Something must be possible with the help of available literature and other public sources. Freemasons describe Freemasonry as "a peculiar system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols". Ethics, morality or moral philosophy refer to rules provided by an external source such as codes of conduct or principles put forward in religions or philosophical systems. Morality is ultimately a personal compass of right and wrong. As a system of morality which developed in the 18th century, freemasonry most likely applies concepts and ideas derived from traditional virtue ethics, which goes back to Aristotle (384-322 BCE) and his Nicomachean Ethics. How to study the allegories and symbols of freemasonry? We need some instruments to study allegories, symbols and the morality of freemasonry. Hermeneutics as the theory and methodology of interpretation can be used to study the rituals and symbols of freemasonry. Semiotics as the study of meaning-making, the study of sign processes and meaningful communication can be applied to the symbols of freemasonry. Hermeneutics and semiotics can be used to find the deeper sense or underlying meaning, hidden under the surface, which the Greeks called hypónoia. Hermeneutics has a long tradition but it also changed over time in its methods and goals. Johann Conrad Dannhauer (1603-1666 CE) wrote the first systematic textbook on general hermeneutics. Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (1768-1834 CE) can be considered to be the father of modern hermeneutics as a general study. For Schleiermacher interpreting a text deals with the inner thoughts of the author and the language that the author used in writing the text. Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900-2002) CE) in his Wahrheit und Methode (1960) deployed the concept of "philosophical hermeneutics" and abandoned the idea of being able to find a connection with an author's thoughts which led to the creation of a text. Julia Kristeva (b. 1941) put forward the concept of intertextuality: "any text is constructed as a mosaic of quotations; any text is the absorption and transformation of another" (Kristeva, 1986). Kristeva developed her own idea of intertextuality from reading the work of Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975 CE). Following Bakhtin's discussion of dialogism, Kristeva postulates that any literary text inserts itself into the set of all texts. In this sense, any text is a part of a cultural continuum that extends to the very beginnings of humankind. The cultural (mythical) roots of Western culture can be traced back to the the Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, the Jewish תַּנַ"ךְ (Tanakh), and the Greek Iliad and Odyssey. Even the Indian Mahābhārata and the Bhagavad Gita (Ch. 23-40 of the 6th book of the Mahābhārata) would be interesting to relate to the symbols and rituals of freemasonry. Every text can be regarded as nothing more than a footnote to (the themes of) these ancient texts, like, according to Alfred North Whitehead, all (Western) philosophy consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. In the context of freemasonry this could lead us to the roots of the Indo-European tradition which freemasons have used and depended upon to define their symbols and rituals. One can also study the rituals (texts) of freemasonry by taking into account their historic context as in historicism or take another approach such as structuralism or both. Freemasonry makes extensive use of myths in its rituals, which requires studying mythology in order to understand the deeper meaning of its message. Joseph Campbell (1904-1987 CE) and his work in comparative mythology and comparative religion provides inspiration to connect the allegories and symbols of freemasonry with Indo-European and Semitic mythological traditions. The concept of the monomyth or hero's journey from The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) can be applied to the rituals of freemasonry. For the study of the topological relations of the masonic temple and masonic rituals as techniques for remembering images for words, the concept of the memory temple can be used in the tradition of the 'ars memorandi'. Frances Yates (1899-1981 CE) wrote about memory temples in The Art of Memory (1966). (see also Hermeneutics, Richard E. Palmer, Northwestern University Press, 1969 and The Disciplines of Interpretation: Lessing, Herder, Schlegel and Hermeneutics in Germany, 1750-1800, Robert Scott Leventhal, Walter de Gruyter, 1994, p. 82 and The Problem of Objectivity in Gadamer's Hermeneutics in Light of McDowell's Empiricism, Morten S. Thaning, Springer, 2015, p. 16 and Modern Critical Theory and Classical Literature, Irene J. F. De Jong, J. John Patrick Sullivan, BRILL, 1994, p. 153 and The Kristeva Reader, "Word, Dialog and Novel", Julia Kristeva, ed. Toril Moi, Columbia University Press, 1986, pp. 34-61 and The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell, New World Library, 2008 and The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, Christopher Vogler, Michael Wiese Productions, 2007 and The philosophy of freemasonry: It's Mythical Structure, Ronald Paul Ng, First presented at Fidelity Lodge No. 8469 UGLE, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on 2nd October, 2006 and Ancient and Medieval Memories: Studies in the Reconstruction of the Past, Janet Coleman, Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 417 and Art and Magic in the Court of the Stuarts, Vaughan Hart, Routledge, 2002, p. 81 and Three uses of memory in freemasonry, J. Scott Kenney, Burns Lodge No. 10, Grand Lodge of Nova Scotia, Canada).

The rituals and symbols of freemasonry have both a literary meaning and a hidden meaning. How to find out what is meant by a symbol and an allegory? A symbol is "something that stands for, represents, or denotes something else (not by exact resemblance, but by vague suggestion, or by some accidental or conventional relation)". Understanding the meaning of a symbol is part of studying a certain tradition and culture in its historic context. The ancient Greek Doric order of architecture symbolizes strength, while the sprig of acacia reminds of immortality. In order to express a complex idea or image, freemasonry uses a figurative language to express its message. Allegories are narratives with an underlying message. An allegory is a story that can be understood both literally and as referring to some external already know situation and requires additional knowledge in order to understand its meaning. An allegory is also concerned with the exposition of theoretical truths rather than practical exhortation. The word "allegory," is derived from the Greek "ἄλλος", meaning "other," and "ἀγορεύω," meaning "proclaim.", which means 'to speak something different'. An allegory expresses a concept using a different word, similar to a metaphor. Contrary to a metaphor, the shift of meaning is often deep and hidden. It originally referred to a figure of speech that Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE) defined as a "continuous stream of metaphors." Philo of Alexandria used allegory to bridge the divide between revelation in the Jewish Torah and Greek Platonic philosophy. Clement of Alexandria and Origen of Alexandria would use allegorical interpretation to unveil the hidden meaning of the Christian Bible (see Origen and The Holy Scriptures). According to Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE), allegory is a mode of speech in which one thing is understood by another. Thomas Aquinas would also contribute to allegorical scriptural interpretation. Besides a literal sense, he described the spiritual sense as having a threefold division which includes the allegorical sense (typology), the moral sense, and the anagogical sense, which refers to our ultimate destiny Allegory in the Middle Ages distinguished four types of interpretation or allēgoria: figurative allegory, narrative allegory, moral (or tropological) allegory and typological allegory each with its own hidden layer of meaning. Figurative allegory serves to make specific typological connections between representations in the ritual and its participants. Narrative allegory uses the narrative's temporal shape and the temporal and causal development of a story or ritual. Moral (or tropological) allegory deals with how one should act in the present, the "moral of the story". Typological allegory deals with interpretation which is concerned with the links between subjects referred to in texts or rituals. Several types interpretation point to a different meaning which can all be present at the same time in the same text or ritual. The literal/historical meaning points backwards to the past, the allegoric points forwards to the future, the moral (tropological) points downwards to the moral/human, and the anagogic (ἀναγωγή) interpretation points upwards to the spiritual/heavenly. There are several types of allegory or layers of meaning which can be hidden in the rituals of freemasonry. Allegory and symbolism makes freemasonry resemble an onion with several layers of meaning or a matryoshka doll. Allegory hides the truth from the ignorant, who are prevented from the knowledge of the truth. At the same time it always reveals what is new to the renewed eyes of those who are initiated and grow in its mysteries. The sequence of the three degrees of freemasonry is allegorical, and most likely represents the course of human existence. The building of the Temple in freemasonry prefigures the erection of man's moral edifice, etc. . There is also the allegory of nature unveiling itself for science, such as in the statue Nature se dévoilant à la Science, which refers to the allegory of the Veil of Isis, representing the classical inaccessibility of nature's secrets (see also The allegorical interpretation of the scriptures and Literary Criticism: A New History: A New History, Gary Day, Edinburgh University Press, 2008, p. 85 and Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory, David Herman, Manfred Jahn, Marie-Laure Ryan, Routledge, 2010, p. 11 and The Symbolism of Freemasonry,Albert G. Mackey, 1882).

Information about freemasonry is freely avaiable on the Internet, in books and other publication, but of course we cannot known if this contains also the so-called secrets of freemasonry. Although some information seems more or less reliable a lot seems to be based on legends and myths. Weeding out the myth and trying to distinguish historical facts from fiction and fantasy is not easy. For a lot of information about freemasonry it can be said that "Se non è vero, è ben trovato" (If it is not true, it is well imagined). The goal is to study freemasonry like any other historical and philosophical subject and to refrain from uncritical adoration or vitriolic demonization. Adoration and demonization may satisfy emotions, but leave the mind unsatisfied. Neither masonophobia nor masonophilia has its place in the study of freemasonry.

Early traces of movements related to freemasonry already existed in England during the Elizabethan era (1558-1603 CE), the rule of the Roman Catholic House of Stuart (1603-1649 and 1660-1688 CE) and the Commonwealth of England (1649 to 1660 CE). Relations developed between masons and nascent democratic movements, as each lodge set up a polity where an individual's standing was meant to be based on merit, rather than on birth or wealth. Freemasonry also became part of the rising cosmopolitan movement of the 17th century and its claim of universal brotherhood (see also The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, Frances Yates, Routledge, 1979 and The Origins of Freemasonry, Facts and Fictions, Margaret C. Jacob, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007 and Strangers Nowhere in the World, The Rise of Cosmopolitanism in Early Modern Europe, Margaret C. Jacob, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006).

Several philosophical and political movements which were active around this time would influence the establishment of speculative freemasonry. Supporters of both the Roman Catholic House of Stuart and the Protestant House of Hannover, were involved in the development of early freemasonry. The adherents of the House of Stuart would be moved into the background by the supporters of the House of Hannover. The philosophical and political ideas associated with the Protestant Hannoverians would dominate the establishment of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster in 1717. The Grand Lodge of London and Westminster was founded after the protestant George Louis, elector of Hanover (1660-1727 CE), succeeded to the British crown, as George I on 1 August 1714 and the end of the Jacobite Rising of 1715 by Tory rebels. The first group of "Hannoverian" freemasons were mostly Whigs and Newtonians. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism (see also Aristotle on Politeia in his Athenaion Politeia and Politics) and opposition to the absolute rule of the House of Stuart (divine-right theory of kingship). The Whigs took full control of the government in 1715, and the "Whig Supremacy" would last from 1715 until 1760. It was enabled by the Hanoverian succession of George I in 1714 and the failed Jacobite rising of 1715.In order to claim legitimacy, the legendary history of freemasonry had to start in an ancient 'Golden Age' or in 'Paradise' (FWIW). European mythology has a tradition of stages of human existence, which tend to progress from an original, long-gone age in which humans enjoyed peace, brotherhood, prosperity, and happiness, compared to the current age and miseries of human civilization. Several legends about the origins of freemasonry can be related to this pattern ("argumentum ad antiquitatem"). The legendary history of freemasonry served as a 'mythomoteur' or constitutive myth that provided (modern) freemasonry with a sense of purpose. The legendary history constituted freemasonry through narrative and they bound freemasons into a collective consciousness. Robert Cover (1943-1986 CE) in Nomos and Narrative, wrote that "we inhabit a 'nomos' - a normative universe. We constantly create and maintain a world of right and wrong, of lawful and unlawful, of valid and void". Ernst Cassirer (1874-1945 CE) wrote that myth is “the art of expressing, and that means of organizing, [man’s] most deeply rooted instincts, his hopes and fears.” (see also The Supreme Court, 1982 Term -- Foreword: Nomos and Narrative, Robert M. Cover, Faculty Scholarship Series, 2705, Yale Law School, 1983 and The myth of the state, Ernst Cassirer, Yale University Press, 1977).

There are two story lines, one in the Egyptian-Graeco-Roman tradition, the other one in the Egyptian-Semitic tradition. The Greeks and Romans had their Ages of Man and the Abrahamic traditions have their paradise in the Garden of Eden. In The Constitutions of the Free-Masons (1723 and 1738) the history of freemasonry started with Adam in the Garden of Eden. The oldest (European) legends go back to ancient Egypt. Several legends state that the origin of Freemasonry go back to the Mystery Schools of Ancient Egypt. The Greek philosopher Pythagoras is traditionally thought to have been initiated in the Egyptian mysteries, where he learned about geometry. Some relate the origins of freemasonry to the Greco-Roman mysteries, such as the Eleusinian Mysteries of Greece or Roman Mithraism. Some relate Freemasonry to the Associations in Ancient Rome, such as the 'collegia opificum' (trade guilds) with the 'Collegia Fabrorum', which were believed to have been instituted by Numa Pompilius (753-673 BCE). Some relate freemasonry to the Essenes. Johann Georg Wachter (1673-1757 CE) in his Der Spinozismus im Judentum: Oder die von dem heutigen Judentum und dessen geheimen Kabbala vergötterte Welt (1699 CE), puts the Essenes in the natural theology and Deist tradition whose tradition could be traced back to Egypt and Jewish Kabbalah (Hanegraaff, 2014, p. 213; Florian, 1999, pp. 282-286; Freemasons, 1877, p. 122). Karl Friedrich Stäudlin (1761-1826 CE) is his Geschichte der Sittenlehre Jesu linked the Essenes to Pythagoras (Stäudlin, 1799, pp. 484-485; Hanegraaff, 2014, p. 214; T. S. Beall, 2004, p. 132; W.A. Laurie, 1859, p. 22). Freemasonry as an organization is also believed to have its roots in Rosicrucianism, which arose in (Protestant) Europe in the early 17th century and which was in itself an mixture of (Christian) Kabbalah, Hermeticism, alchemy, and mystical Christianity (Semitic/Abrahamic tradition) (Frances Yates, 2001). Thomas Paine (1736-1809 CE), in his essay On The Origin Of Free Masonry (1818 CE), traced the origins of Freemasonry to the religion of the ancient Druids (S. Afsai, 2010). (see also History of Freemasonry 1898, Volume 2, Albert G. MacKey, William R. Singleton, Kessinger, p. 485 and Stolen Legacy, Ch. VII: The Curriculum of the Egyptian Mystery System, George G. M. James, 1954 and The Hidden Life In Freemasonry, Introduction, C. W. Leadbeater, Cornerstone Book Publishers, 2007 and Esotericism and the Academy Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture, Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Cambridge University Press, 2014 and Die Mysterien der Aufklärung. Esoterische Traditionen in der Freimaurerei?, Maurice Florian, in: M. Neugebauer-Wölk (Hg.), Aufklärung und Esoterik (Studien zum achtzehnten Jahrhundert 24), Hamburg, 1999, pp. 274-287 and Josephus' Description of the Essenes Illustrated by the Dead Sea Scrolls, Todd S. Beall, Cambridge University Press, 2004 and Pythagoreans and Essenes: structural parallels, Justin Taylor, Peeters, 2004 and The History of Free Masonry and the Grand Lodge of Scotland, William Alexander Laurie, Seton & Mackenzie, 1859 and Liturgy of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry: For the Southern Jurisdiction of the United States, Volume 3 Freemasons, United States, Scottish Rite, Supreme Council for the Southern Jurisdiction, 1877 and Geschichte der Sittenlehre Jesu, Vol. I, Karl Friedrich Stäudlin, Im Vandenhoeck-Ruprechtischen Verlage, 1799 and The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, Frances Yates, Routledge, 2001 and Thomas Paine's Masonic Essay and the Question of His Membership in the Fraternity, Shai Afsai, Philalethes 63:4; 2010; pp. 140-141).

The architectural symbolism of freemasonry goes back to Solomon's temple, the Knights Templar and the medieval masons' lodges. Legend has it that Freemasonry was founded at the building of Solomon's temple by King Solomon (ca. 970-ca. 931 BCE), which itself was inspired by Egyptian Temples. Isaac Newton (1642-1727 CE) believed Solomon's temple to be an example of the ancient Prytaneion (Betty Jo Teeter Dobbs, 2002, p. 153 and Stephen G. Miller, 1977). Solomon's temple also relates Freemasonry to the Knights Templar. Chevalier Andrew M. Ramsay (1686-1743 CE) Grand Orator of the Stuart freemasonry with his Oration of 21 March 1737 (or 'Discourse of le Chevalier Ramsay given at the St.John's Lodge on 27th December 1736') would relate Stuart freemasonry to the Knights Templar. The legend of the Knights Templar would also relate freemasonry to the Essene and Pythagorean tradition (Todd S. Beall, 2004, p. 132). The Esseness learned about Pythagoreanism, and the Knights Templar brought this knowledge to Scotland where it became part of Scottish freemasonry (Hanegraaff, 2014, pp. 215-216). During the early medieval period, the Magistri Comacini were Lombard stonemasons organized in guilds. The Old Charges relate freemasonry to the masons' lodges which were involved in building the European cathedrals and which dealt with geometry (architecture) as one of the seven liberal arts (Medieval and Greco-Roman tradition). (see also Chapters of Masonic History, Part VI. Freemasonry and the Comacine Masters, H.L. Haywood, The Builder Magazine, October 1923 - Volume IX - Number 10 and The Janus Faces of Genius: The Role of Alchemy in Newton's Thought, Betty Jo Teeter Dobbs, Cambridge University Press, 2002 and Josephus' Description of the Essenes Illustrated by the Dead Sea Scrolls, Todd S. Beall, Cambridge University Press, 2004 and The Prytaneion: Its Function and Architectural Form Hardcover, Stephen G. Miller, Univ of California Press, 1977 and Esotericism and the Academy Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture, Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Cambridge University Press, 2014).

The protestant reformation and the European wars of religion would cause bloodshed and social and political instability in Europe. The Thirty Years' War would ravage central Europe. The English Reformation and the English Civil War (1642-1651 CE) would cause destruction and bloodshed on the Islands. Several attempts were made to resolve the situation and to live thorough desperate times. Justus Lipsius (1547-1606 CE) wrote his De Constantia in publicis malis (1583 CE) as an attempt to reconcile Stoicism and Christianity, which became known as Neostoicism (R. B. Wernham, 1968). Guillaume du Vair (1556-1621 CE) wrote his neostoic La Philosophie morale des Stoiques (1585 CE) and De la constance et consolation ès calamités publiques (1589 CE). During the early 17th century Rosicrucianism, associated with Lutheranism, (Christian) Kabbalah, Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, alchemy, and mystical Christianity, was believed to be a a philosophical secret society resembling an early predecessor of freemasonry. Although most historical documents of 17th century freemasonry are lost, it was most likely associated with the Catholic House of Stuart in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. The members of the House of Stuart tended to be carriers of Freemasonry which would (presumably) develop into Ecossais freemasonry during their exile after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Another element was the role of the new educated urban classes of urban England in public affairs and government. Among the founders of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster were members of the Royal Society, and Huguenot emigres, who flocked to England after the Revocation of the Edicts of Nantes by Louis XIV (1638-1715 CE) in 1685 CE (see also The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 3, Counter-Reformation and Price Revolution, 1559-1610, R. B. Wernham, CUP Archive, 1968, p. 443) and The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, Frances Yates, Routledge; 2nd edition, 2001 and Restoring the Temple of Vision: Cabalistic Freemasonry and Stuart Culture, Marsha Keith Schuchard, BRILL, 2002 and Freemasonry and the House of Stuart, Albert Gallatin Mackey, William R. Singleton, Lightning Source, 2005 and The History of Freemasonry: Its Legendary Origins, Albert Gallatin Mackey, Courier Corporation, 2012, p. 279 and The articulate citizen and the English Renaissance, Arthur B. Ferguson, Duke University Press, 1965, pp. 402-409).

Robert Moray (1608 or 1609-1673 CE) was initiated into Freemasonry on 20 May 1641. Elias Ashmole (1617-1692 CE) on 16 October 1646 was admitted as a Freemason. Robert Moray and Elias Ashmole, both supporting the Roman Catholic House of Stuart, were part of the founding members of the Royal Society (see also Restoring the temple of vision: Cabalistic freemasonry and Stuart culture, Marsha Keith Schuchard, p. 581, 2002). Sir Robert Moray (1608 or 1609-1673 CE) was the first acting president of the Royal Society from its first meeting on 28 November 1660 to its incorporation on 15 July 1662. He presented the Charter of the Society to Charles II (1630-1685 CE) and obtained his approval (see also Freemasonry and the Birth of Modern Science, Robert Lomas, Fair Winds Press, 2003 and Sir Robert Moray, F.R.S. (1608?-1673), D. C. Martin, Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London Vol. 15, (Jul., 1960), pp. 239-250). The Bohemian Revolt (1618-1620 CE) would start the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648 CE). The defeat of Bohemian protestants in the Thirty Years' War would cause an influx of refugees into protestant England. People like Amos Johannes Comenius (1529-1670 CE) and Samuel Hartlib (ca. 1600-1662 CE) would bring new ideas to England (The Crisis of the Seventeenth Century: Religion, the Reformation and Social Change, Hugh Trevor-Roper, 1967 and From Counter-Reformation to Glorious Revolution, Hugh Trevor-Roper, 1992). Amos Johannes Comenius (1529-1670 CE) in his Via Lucis, Vestigata & Vestiganda (The Way of Light) (1641) put forward the pursuit of higher learning and spiritual enlightenment bound together. He referred to reading three books: liber homo, liber mundi, liber Theos. His magnum opus was De Rerum Humanarum Emendatione Consultatio Catholica (General discourse on the emendation of human affairs, or Consultatio) (1670) contained a plan for the creation of a Christian society. Comenius discussed the universal education for all men and the art of teaching was intended to be the core of pansophy (Jan Amos Comenius, Jean Piaget, UNESCO, International Bureau of Education, vol. XXIII, no. 1/2, 1993, p. 173-96 and Pansophiae prodromus, Jan Amos Comenius, 1639 and Pansophiae diatyposis, Jan Amos Comenius, 1643)).

In the seventeenth century philosophy and theology would undergo profound changes. Early seventeenth century philosophy is often called the Age of Reason or Age of Rationalism and preceded the Enlightenment. Emerging Deism saw God as the Great Architect of the Universe or a God who does not interfere in human affairs, but whose very nature orders and structures all of creation. God's power (potentia Dei) could be described as 'potentia dei absoluta' or 'potentia dei ordinata'. God could either override all that had been done or God was bound by his past actions and could not undo what had been done. Theists adhered to the first view, while Deists preferred the second viewpoint, which had enormous consequences on philosophical and scientific positions. For those who adhered to 'potentia dei ordinata', the world could be known with certainty as God would never chance the laws of nature or undo what had been done (J.R Wigelwsorth, 2009, p. 6-7). Isaac Newton (1642-1727 CE) in the 'General Scholium' of the second edition of his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1713 CE) would put forward a characterization of the "Lord God παντοκρατωρ, or Universal Ruler" against the (passive) Deistic image of God. Deism as a theology can be seen as a successor to the teachings of Giordano Bruno (1548-1600 CE), John Dee (1527-1608 or 1609 CE) and John Amos Comenius (1592-1670 CE), which also advocated a world brotherhood of harmony and peace, but without the risk of offending scientists or (protestant) theologians. The idea of a world brotherhood of harmony and peace goes back to the Cynic and Stoic κοσμοπολίτης, meaning "citizen of the world" (Diogenes Laertius, Βίοι καὶ γνῶμαι τῶν ἐν φιλοσοφίᾳ εὐδοκιμησάντων, VI 63). Jean Bodin (1530-1596 CE), Pierre Charron (1541-1603 CE), and Lord Edward Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648 CE) developed a Deistic view on the position of man and a form of natural religion. Jean Bodin in his Colloquium Heptaplomeres de rerum sublimium arcanis abditis (1683) developed a view on natural religion. Seven speakers represented as many different religions, confessions, and philosophical schools of thought of which the character Toralbe presents natural religion as follows "the laws of Nature and natural religion, which nature inspires in the heart, are sufficient for salvation". Pierre Charron was a close friend of Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592 CE) who was influenced by Pyrrhonic skepticism and Stoicism. Pierre Charron in De la sagesse (1601 CE) wrote about the religious duty of the sage, which influenced the Deists of the seventeenth century and their view on the superstitions of mankind, idolatry and religious ceremonies. De la sagesse presented one of the first modern ethical systems to establish a basis for morality independent of religion, founded essentially on Stoic theories and the recognition and development of humanity's natural character. Edward Herbert of Cherbury wrote De Veritate, prout distinguitur a revelatione, a verisimili, a possibili, et a falso (1624 CE) in which he put forward the common notions of religion in five articles, which became the charter of the English deists. These five articles contained the whole doctrine of the religion of reason, which also formed the primitive (original) religion. What is contrary to these five articles was also contrary to reason. Although there exists revelation beyond reason, the record of a revelation is not itself revelation but only tradition and therefore can never be more than probable (see also De Potentia Dei, Thomas Aquinas, The Newman Press, 1952 and Deism in Enlightenment England, Jeffrey R. Wigelsworth, Manchester University Press, 2009 and The ‘General Scholium’ of the Principia and Isaac Newton's freemasonry, The Alchemy of Science and MysticismCh. 3, Alain Bauer, Inner Traditions, 2007, and Early Deism in France: From the so-called ‘déistes’ of Lyon (1564) to Voltaire’s ‘Lettres philosophiques’ (1734), C.J. Betts, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, pp. 18-20 and Enlightenment Cosmopolitanism, David Adams, Routledge, 2017, p. 13 and Pierre Charron, Renée Kogel, Librairie Droz, 1972, p. 144 and The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Part 2, Volume 2, Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1983, p. 771 and The English Deists: Studies in Early Enlightenment, Wayne Hudson, Routledge, 2015, p. 50 and The life of Edward lord Herbert, of Cherbury, written by himself [ed. by H. Walpole]. With a prefatory memoir, Edward Herbert (1st baron.) 1847, pp. 7-8).

The Enlightenment would put forward concepts such as progress, perfectibility, and cosmopolitanism. The Enlightenment would take a secular and rational turn, away from the esoteric and hermetic tradition of the Renaissance. Giordano Bruno (1548-1600 CE) had visited England in 1583-1584 and he influenced the intellectually and spiritually minded Englishmen (Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Francis A. Yates, The University of Chicago Press and London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1964, pp. 275 ff.). Bruno had been the first major Renaissance figure to call for a broad, tolerant international ethic of world peace and universal brotherhood for which he referred to Egyptian mythology and philosophy. In France the Philosophes, after dislodging the religion of God in favor of the humanistic religion of Man, had to find some replacement for Christian salvation and afterlife. (Anna Lydia Motto, 1993). Also "Without a new heaven to replace the old, a new way of salvation, of attaining perfection, the religion of humanity would appeal in vain to the common run of men" (Anna Lydia Motto, 1993). The Enlightenment in Britain retained an element of millenarianism or "a belief in a new heaven to replace the old", albeit in a secular or rational form (Carl Becker, 1932). The promise to build a better world on this world before the end of time goes back to Joachim of Fiore (ca. 1135-1202 CE) in his Enchiridion super Apocalypsim and the theory of the three ages of the Babylonian Talmud or 'Vaticinium Eliae' (prophecy of Elijah or Elias) (Lloyd Kramer, Sarah Maza, 2006 and Wilhelm Schmidt-Biggemann, 2007). In Die Erziehung des Menschengeschlechts (1780) Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729-1781 CE), in a revision of Joachim of Fiore's three dispensations, pictured the Enlightenment belief system as the third dispensation after the first and second religious stages shaped by the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament (Jan A. B. Jongeneel, 2009). Unitarinaism or modern Arianism would also be part of the Newtonian movement. Newtonians, such as Isaac Newton, Samuel Clarke (1675-1729 CE), and William Whiston (1667-1752 CE) would be unitarinans or antitrinitarians. In 1712 Samuel Clarke would publish The Scripture Doctrine of the Trinity in which he put forward that Scripture pointed towards a singular Arian-like God instead of the Trinitarian view. Whiston, who succeeded Newton as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, would be expelled from the university as a result of his unorthodox religious views. The emergence of natural religion would accompany the rise of Newtonianism. Isaac Newton had put forward the argument from design: "that the physical laws he had uncovered revealed the mechanical perfection of the workings of the universe to be akin to a watch, wherein the watchmaker is God." While Isaac Newton held the opinion that gravity was an aspect of divine activity in the world and could not have emerged out of a mere material universe, Newtonianism would open Pandora's box with regard to the relation between God and the laws of nature and matter (Wigelsworth, 2009, p. 80). Enlightenment philosophy and theology would discuss the relation between God and the laws of nature and matter. With regard to the danger of (natural) philosophy for religion we may remember the words of Tertullianus in his Liber De Praescriptione Haereticorum: "Fuerat Athenis et istam sapientiam humanam affectatricem et interpolatricem ueritatis de congressibus nouerat, ipsam quoque in suas haereses multipartitam uarietate sectarum inuicem repugnantium. Quid ergo Athenis et Hierosolymis? quid academiae et ecclesiae? quid haereticis et christianis?". The rationalism of the Enlightenment would be the subject of several publications and theological, philosophical and moral development. Anthony Collins (1676-1729 CE) and John Toland (1670-1722 CE) were part of a group of radical free thinkers. Collins put forward the autonomy of reason, religious freedom and an aversion to religious persecution. John Toland (1670-1722 CE) was a philosopher most famous for his book Christianity Not Mysterious; or, A treatise Shewing That There Is Nothing in the Gospel Contrary to Reason, nor above It, and That No Christian Doctrine Can Be Properly Call'd a Mystery (1696) in which, as a deist, Toland opposed the subordination of reason to revelation. In Christianity Not Mysterious, Toland applied John Locke's (1632-1704 CE) philosophy of common sense to religion. Whereas Locke suggested that Christianity is reasonable, Toland took a decisive step in arguing that reasonable meant not mysterious. The implicit, heretical conclusion is that revelation cannot contradict reason, since "whoever tells us something we did not know before must insure that his words are intelligible, and the matter possible. This holds good, let God or man be the revealer". Toland attributed theological mysteries to scriptural misinterpretations of priests, and in this he anticipates 18th-century exponents of natural religion (see also English Deism: Its Roots and Fruits, John Orr, 1934). In 1704 Toland published his Letters to Serena, which, inspired by Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (TTP), dealt with superstition, prejudice, notions of an 'immortal soul' and the autonomy of the material world with regard to 'motive force'. For Toland, motion did not require a transcendent or transitive cause of motion, which emphasized the autonomy of the material world and therefore a materialist conception of nature. The viewpoint held by Toland would develop into eighteenth century 'vitalistic materialism', which stated that motion is inherent in matter and that Newton's science had proven it. Newtonian science would move away from Newton's own metaphysics, which still located the source of motion in immaterial forces of divine origin (Margaret C. Jacob, 2013). Further developments would lead, besides the idea of self-moving matter to the notion of thinking matter. Toland also wrote the Pantheisticon, sive formula celebrandae sodalitatis socraticae (1751), which is a script for a liturgy of a Pantheist club or Socratic Society (see also John Toland: His Methods, Manners, and Mind, Stephen H. Daniel, 1984). The concept of "pantheism" was used by Toland to describe the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677 CE). Toland in his Pantheisticon refers to 'l'honnête homme' who will be 'l'homme parfait'. The "honnête homme" resembles the καλὸς κἀγαθός of ancient Greece. Ischomachus, the gentleman-farmer, in the dialog Οἰκονομικός by Xenophon was the model for the καλὸς κἀγαθός. Toland also translated the Spaccio de la bestia trionfante (The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast) of Giordano Bruno (1548-1600 CE) (J. A. I. Champion, 1992, p. 150-151). Toland in his translation, presents the Spaccio as a work dealing with the corruption of ancient religion (prisca theologia) and the need of religious reformation based on the 'intelligible, useful, necessary, and unalterable Law of Nature' in order to establish a 'civil theology' (theologia civilis). In Socinianism Truly Stated, by a pantheist (1705), Toland was the first to use the word pantheism: "The sun is my father, the earth my mother, the world is my country and all men are my family" (Paul A. Harrison, 2004, p. 29). Thomas Kuhn (1922-1996 CE) would put forward his view on 'l'honnête homme' in his Tradition mathématique et tradition expérimentale dans le développement de la physique (1975). In 1713 William Derham (1657-1735 CE) published his Physico-Theology and Astro-Theology in 1714, which both dealt with teleological arguments for the being and attributes of God. In 1709 Henry Sacheverell (1674-1724 CE) published The Perils of False Brethren, in Church, and State, which was an attack on Whigs and moderate Anglicans such as latitudinarians. He not only attacked the "neutrality in religion" put forward by Deists, but also natural theology which attempted to explain religion in "new-fangl'd terms of modern philosophy". Sacheverell's sermon would play an important role in the struggle for power between Whigs and Tories. Whigs would support the ascent to the throne of the House of Hannover, while die-hard Tories would still support the Jacobite cause (W.A. Speck, 1977, p. 150 and Ian R. Christie, 1987). In 1713 Anthony Collins published A Discourse of Freethinking, occasioned by the Rise and Growth of a Sect called Freethinkers, in favor of religious toleration, freedom of thought and against superstition (Wigelsworth, 2009, p. 119). It was in this political, theological and philosophical environment, a new Whig-Hanoverian and Newtonian freemasonry was established (see also The Heavenly City of the Eighteenth-Century Philosophers, Carl L. Becker, New Haven, 1965, p. 129 and Essays on Seneca, Anna Lydia Motto, P. Lang, 1993, p.37 and A Companion to Western Historical Thought, Lloyd Kramer, Sarah Maza, Wiley, 2006, p; 83 and Philosophia perennis: Historical Outlines of Western Spirituality in Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Thought, Wilhelm Schmidt-Biggemann, Springer Science & Business Media, 2007, p. 402 and Marketing Apocalypse: Eschatology, Escapology and the Illusion of the End, Jim Bell, Stephen Brown, David Carson, Routledge, 2003, p. 30 and Jesus Christ in World History: His Presence and Representation in Cyclical and Linear Settings, Jan A. B. Jongeneel, Peter Lang, 2009, p. 326 and Egyptian elements in Die Zauberflöte (K. 620) by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791 CE) and (see also Freemasonry: A Very Short Introduction, Andreas Önnerfors, Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 46 and Enlightenment Cosmopolitanism, David Adams, Routledge, 2017, p. 13 and The Pillars of Priestcraft Shaken: The Church of England and Its Enemies, 1660-1730, J. A. I. Champion, CUP Archive, 1992 and Deism in Enlightenment England, Jeffrey Wigelsworth, Manchester University Press, 2009 and The radical enlightenment and freemasonry: where we are now, Margaret C. Jacob, Philosophica 88 (2013) pp.13-29 and Elements of Pantheism, Paul A. Harrison, 2004 and Stability and Strife: England, 1714-1760, W. A. Speck, Harvard University Press, 1977 and Dr. John Theophilus Desaguliers and The Newtonian System of the World, Philalethes: The Journal of Masonic Research & Letters, Vol.71, No.3, (Summer 2018), pp.94-101 and The Tory Party, Jacobitism and the 'Forty-Five: A Note, Ian R. Christie, The Historical Journal, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Dec., 1987), pp. 921-931).

The 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713 CE) wrote The Moralists a Philosophical Rhapsody a recital of certain conversations on natural and moral subjects and attempted to motivate people to become better by showing them the goodness of human nature (see also The British Moralists on Human Nature and the Birth of Secular Ethics). Shaftesbury also reflected on the nature of philosophy in his Askêmata notebooks (hypomnemata), inspired by the Roman Stoics Epictetus (ca. AD 55-135 CE) and Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE) (Sellars, 2016). The French Huguenot Pierre des Maizeaux (1666/1673-1745 CE), who lived in exile in London, was involved with the Huguenot information center based at the Rainbow Coffee House, which provided a meeting place for freemasons and French refugee Huguenots. Newtonianism stood for the search for a "first cause" through natural philosophy and scientific work, which laid the groundwork for the great scientific revolutions and discoveries during the Enlightenment. It was Isaac Newton's (1642-1727 CE) idea of a quest for moral science through natural philosophy that became the theme of the Enlightenment and freemasonry and which he put forward in his Opticks (book 3): "And if natural philosophy in all its Parts, by pursuing this Methods, shall at length be perfected, the Bounds of Moral Philosophy will also be enlarged. For so far as we can know by natural Philosophy what is the first Cause, what Power he has over us, and what Benefits we receive from him, so far our Duty towards him, as well as that towards one another, will appear to us by the Light of Nature". The nature of freemasonry was influenced by these new ideas, which would change the nature of freemasonry from a Roman Catholic to a Protestant and Newtonian movement. At the time of the founding of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster, the Leibnizian-Newtonian controversy (relationist versus absolutist) was going on between their different philosophical world views on the nature of God (intellectualist versus voluntarist), matter (mechanistic versus a vitalistic view of the relationship between matter and force), and force (force versus vis viva or anima mundi). Most of the debate went on between Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716 CE) and Samuel Clarke (1675-1729 CE), a friend of Newton and became known as the Leibniz-Clarke correspondence. The disagreement between Leibniz and Samuel Clarke was as much about free will and religion as natural philosophy. Clarke also wrote The Scripture doctrine of the Trinity (1712 CE) concerning the doctrine of the Trinity. The advancement of science necessitated a more open approach to natural philosophy or "Philosophiae Naturalis". In 1679 Johann Sturm (1635-1703 CE) published a disputation De Philosophia Sectaria Et Electiva Dissertatio Academica against philosophical sectarianism and in favor of a more general method of philosophical inquiry, eclecticism (philosophia eclectica or electiva) (Thomas Ahnert, 2002). In 1688 Robert Boyle (1627-1691 CE) published his Tractatus de ipsa natura, sive Libera in receptam naturae notionem disquisitio ad amicum on natural philosophy. The experimental method put forward by Sturm and Boyle was meant to end fruitless verbal contests about questions of natural philosophy and allow them to be resolved by the organized and institutionalized observation of nature in the presence of witnesses (naturae scrutatores) (Thomas Ahnert, 2002). The "philosophia sectaria" or mere speculative argument by philosophical sects inevitably led to disagreements among natural philosophers, because its conclusions were not verifiable by experiments conducted before an audience of witnesses. In 1697 Sturm published his Physica Eclectica which emphasized the need for an undogmatic philosophical eclecticism for an experimentalist natural philosophy. Both Boyle and Sturm emphasized the limited and provisional nature of philosophical theories, which reflected their shared belief in the limits of human reason (Jan W. Wojcik, 2009). Any attempt to move beyond establishing consensus on strictly observable phenomena violated the limits of natural philosophical explanation. Going beyond observable phenomena or the visible structure of matter would lead natural philosophical into the domain of metaphysics. The discussion on natural philosophical would shape the development of experimental science in the Royal Society, the Scrutatorum Naturae Regium Concilium in Paris, the Collegia Eruditorum in Rome, the Collegium Experimentale in Altdorf, and the Accademia del Cimento in Florence, etc. . The Royal Society's motto was a quotation from Horatius's Epistulae (I, I, 14): "Nullius addictus iurare in verba magistri, – quo me cumque rapit tempestas, deferor hospes." ("(being) not obliged to swear allegiance to a master, wherever the storm drags me to, I turn in as a guest."). The motto reflected the anti-sectarian aims of the Royal Society and its concern with the definition of reliable testimony. The Royal Society's motto "Nullius [addictus] in verba [iurare magistri]“ referred to the "philosophia eclectica or electiva" as opposed to the "philosophia sectaria" (Haakonssen, 2006, p. 148). The philosophical preoccupation with the limits of reason and the harmful effects of philosophical sectarianism and dogmatism not only had a profound influence on the development of science, but also on religious tolerance. Religious intolerance (sectarianism) in France would lead to an influx of Huguenots in England. The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685 CE) revoked the Edict of Nantes (1598 CE), which had granted the Huguenots the right to practice their religion without persecution from the state. In France, the Huguenot polemic against the papacy, and that of Jansenism against the semipelagianism of the Roman Catholic church would be silenced. The Edict of Fontainebleau would give the deathblow to French Reformed theology, but would lead to the naturalism, atheism, and materialism of the French Enlightenment (J. H. Kurtz, 1893, Ch. III, I, 11). The Edict of Fontainebleau would cause a large number of Protestants to leave France, among them John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683-1744 CE), who would play an important role in the foundation of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster and early Newtonianism. Desaguliers became Isaac Newton's experimental assistant in 1713, and a fellow of the Royal Society in 1714. He wrote Physico-mechanical lectures, or, An account of what is explain'd and demonstrated in the course of mechanical and experimental philosophy (1734). The Grand Lodge of London and Westminster would be founded in 1717, during the Presidency of the Royal Society by Isaac Newton from 1703 until 1727 CE and Desaguliers would be elected as the third Grand Master of the 'Premier Grand Lodge of England' in 1719. Modern freemasonry would come into existence in an environment of "philosophia eclectica or electiva" and "theologia eclectica" in order to overcome philosophical and theological sectarianism (A. J. Bueno, 2016, p. 226). In this eclectic context we could also refer to 1 Thessalonians 5:21: "πάντα δοκιμάζετε τὸ καλὸν κατέχετε" (see also Shaftesbury, Stoicism, and Philosophy as a Way of Life, John Sellars, Sophia, September 2016, Volume 55, Issue 3, pp. 395-408 and Aux origines de la franc-maçonnerie: Newton et les newtoniens, Alain Bauer, Éditions Dervy, 2003 and The Newtonian system of the world, the best model of government: an allegorical poem, John Theophilus Desaguliers, Printed by A. Campbell, for J. Roberts, 1728 and John Theophilus Desaguliers: A Natural Philosopher, Engineer and Freemason in Newtonian England, Audrey T. Carpenter, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011 and Moral Philosophy and Newtonianism in the Scottish Enlightment, Mark H. Waymack, Johns Hopkins University, 1986 and Newton and Newtonianism: New Studies, J.E. Force, S. Hutton, Springer Science & Business Media, 2006, p.224 and The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-century Philosophy, Volumes 1-2, Knud Haakonssen, Cambridge University Press, 2006 and The Culture of Experimentalism in the Holy Roman Empire: Johann Christoph Sturm (1635-1703) and the Collegium Experimentale, Thomas Ahnert, 2002 and Robert Boyle and the Limits of Reason, Jan W. Wojcik, Cambridge University Press, 2009 and Theologia eclectica, moralis et scholastica, Eusebius Amort, Veith, 1752 and Recuperation of Theological Principles against Ideo-logicist Incompetence, Book 3, A. J. Bueno, Strategic Book Publishing & Rights Agency, 2016 and Church History, Vol. 3 of 3, J. H. Kurtz, Hodder and Stoughton, 1893).

The foundation of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster on 24 June 1717 can be regarded as an English usurpation of the Scottish Stuart tradition of freemasonry, presenting itself as the legitimate heir of the (Stuart) masonic tradition. The foundation of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster in 1717 took place during the era which witnessed the end of the Aristotelian dominance of philosophy in Europe, the rise and fall of Cartesianism, the emergence of "experimental philosophy" (later called "empiricism" in the nineteenth century) in Great Britain, and the development of numerous experimental and mathematical methods for the study of nature. The early eighteenth century marked the final transition of absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy in Great Britain after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. It also coincided with the development of the Protestant Christian view of natural law in the Bill of Rights of 1689. The Act of Settlement of 1701, disqualified anyone who becomes a Roman Catholic, or who marries one, to inherit the throne of England and Ireland. The Acts of Union of 1707 joined the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland into Great Britain. Newtonianism and the ascent to the throne of Great Britain of the House of Hanover with George I of Great Britain (1660-1727 CE) provided the philosophical and political background for the creation of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster. Besides being king of Great Britain, George I was also ruler of the continental Herzogtum Braunschweig-Lüneburg, which was part of the Sacrum Romanum Imperium. The Jacobite rising of 1715 was an attempt to regain the throne by James Francis Edward Stuart (Old Pretender). In January 1717 a Swedish-Jacobite plot was discovered in which Charles XII of Sweden would launch an invasion of Scotland in order to restore James Francis Edward Stuart to the Stuart throne. Jacobite freemasons were involved in the plot, which made it necessary to for the Hanoverian freemasons to respond. The foundation of the new Grand Lodge was an attempt to get rid of the old Jacobite Scottish Masonic heritage and to become acceptable for the new Hanoverian rulers. Freemasonry had to shed its Stuart heritage and re-emerge as a loyal Hanoverian fraternity. The foundation of modern freemasonry was a political and religious (Protestant) act related to the the ascent to the throne of Great Britain of the Protestant House of Hanover and Whig policy, combined with the rise of Newtonianism in England. The rise of the new type of freemasonry would be closely related to the triumph of Newtonianism and Hanoverian and Whig politics. The old Scottish-Irish-Stuart traditions (Antients) would get into conflict with the new Whig-Hanoverian freemasons (Moderns) (see also A Concise History of Freemasonry, Robert Freke Gould, Frederick Joseph William Crowe, Macoy Pub. & Masonic Supply Company, 1924, p. 297 and Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717-1927, Jessica L. Harland-Jacobs, UNC Press Books, 2012 and Freemasonry and the Birth of Modern Science, Robert Lomas, Fair Winds Press, p. 265-270 and 1717 and the invasion that never was and Les Rivalités Maçonniques et la Bulle In Eminenti, Marsha Keith Schuchard, La Règle d’Abraham, 25 (2008), pp. 3-48 and Anteckningar till Konung Gustaf IIIs Historia, Elis Schröderheim, 1851, p. 81 and La Crise du Nord au Début du XVIIIe Siècle, Claude Nordmann, 1962, 10, pp. 152-153 and Mystiskt brödraskap-mäktigt nätwerke, Andreas Önnerfors, ed., 2006).

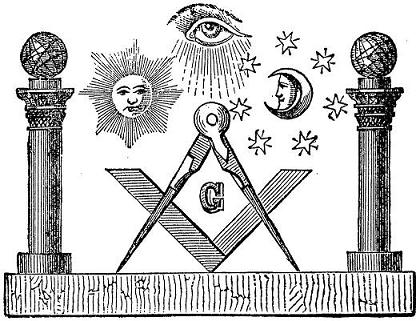

The new Grand Lodge and its concept of Freemasonry, together with the Royal Society, would become a political, scientific and philosophical instrument to spread the ideas of Newtonianism (physico-theology) and constitutional monarchy throughout Great Britain and Europe. The principles of freemasonry would become an inspiration for philosophical, political and religious reform in Great Britain, America and Europe. Besides the Royal Society there were close connections with other learned societies such as the Royal College of Physicians; the Society of Apothecaries; the Society of Antiquaries; and the Spalding Society. The time period between the publication of the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687 CE) and On the Origin of Species (1859 CE), saw the development of (Newtonian) physico-theology, a theology based on the constitution of the natural world according to rational and mathematical laws (Denham, 1754). Here the cosmic λόγος (order) of the Greeks, which could be found in the Book of Nature merged with the Judaic component of European culture (word), which were derived from the Jewish Torah and the Christian New Testament. The instruments of Greek geometry, compass and square, symbols of geometrical reasoning and the geometry of nature, would result in scientific Deism, while humanistic Deism was derived from moral-philosophical speculation and the moral nature of man, which could be symbolized by the Bible (see also Newtonianism, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Isaac Newton, 5 July 1687 and The Concise History of Freemasonry, Robert Freke Gould, Courier Corporation, 2012, p. 207 and The Foundations of Modern Freemasonry: The Grand Architects: Political Change and the Scientific Enlightenment, 1714-1740, Ric Berman, Sussex Academic Press, 2012, p. 112 and Physico-theology: Or, A Demonstration of the Being and Attributes of God, from His Works of Creation, William Derham, W. Innys and J. Richardson, 1754 and Newtonian Physico-Theology and the Varieties of Whiggism in James Thomson's The Seasons, Philip Connell, Huntington Library Quarterly, Vol. 72, No. 1 (March 2009), pp. 1-28 and Science and Religion, 1450-1900: From Copernicus to Darwin, Richard Olson, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, p.125 and Shaftesbury and the Deist Manifesto, Alfred Owen Aldridge, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 41, No. 2 (1951), pp. 297-382).

Officially, the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster, the first Grand Lodge of the modern era was founded on St. John the Baptist's day (symbolizing faith), Thursday 24 June 1717, in London, when 4 Craft Lodges, gathered at the Apple Tree Tavern in London and "constituted themselves a Grand Lodge pro Tempore in Due Form". The four existing Lodges were accustomed to meeting at the Goose and Gridiron Ale-house in St. Paul's Church-yard; Crown Ale-house in Parker's Lane near Drury's Lane; Apple Tree Tavern in Charles Street, Covent Garden; and Rummer and Grapes Tavern in Channel Row, Westminster. The "Rummer and Grapes", appears to have been a lodge of accepted and speculative masons, while the other three lodges were still mainly operative lodges. John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683-1744 CE) was a member of the "Rummer and Grapes" Lodge. There seems to be some symbolic meaning related to the day when the Grand Lodge was founded. The year 1717 is composed of twice 17, a number with a special meaning, as it combines the celestial perfection of 10 (e.g. Pythagorean Tetraktys) with the worldly perfection (achievable by man) symbolized by 7, meaning completeness which is gained only from true insight. St. John the Baptist also stands for faith as opposed to St. John the Evangelist who stands for reason (logos). Faith also refers to the Ladder of Divine Ascent (ca. 600 CE), which Saint John Climacus (ca. 7th century CE) called the "Ladder to Perfection" (see also The Genesis of Freemasonry, Douglas Knoop, Manchester University Press, 1947).

John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683-1744 CE), jointly with colleagues within the orbit of the Grand Lodge, fundamentally altered English Freemasonry to produce an organisation that reflected and reinforced the intellectual and economic transformations then in progress within early eighteenth century English society. The pro-Hanoverian political characteristic of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster was fundamental to its success: demonstrating to the government that Freemasons were now reliable partners in the promotion of the Hanoverian succession and safeguarding of its Whig administration. Several influential Freemasons also held senior office at the Royal Society. It was decided to create a new Charter, which would no longer refer to the Stuart type of freemasonry, but embrace the new Hanoverian rulers. A group of Masons forestalled the new Grand Lodge by having J. Roberts print a Constitution, now called the Roberts Constitutions, dated 1722. They refer to the Seven Liberal Sciences of the classical curriculum (trivium and quadrivium) and the importance of Geometry, which would return in the General Ahiman Rezon of the Antients. George Payne (ca. 1685-1757 CE), in his second term as Grand Master in 1720, wrote the General Regulations of a Freemason (1722). The General Regulations of George Payne would be included in the new Constitutions mainly written by Revd. Dr. James Anderson (1680-1739 CE) in the years 1721-22, under the guidance of Newtonians, such as John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683-1744 CE) and Martin Folkes (1690-1754 CE). The concept of the Constitutions is closely related to the general structure of the Principia of Isaac Newton as it also uses definitions, axioms and propositions. Geometric or Euclidean reasoning is woven into the construction of the Constitutions. Euclid represents the art of geometry and Pythagoras of Samos represents the art of arithmetic, both referring to divine proportion in Nature so eloquently revealed in the Principia. Six years after its formation in 1717, on Sunday 17 January 1723, the Grand Lodge of England approved The Constitutions of the Free-Masons containing the History, Charges, Regulations, & of that most Ancient and Right Worshipful Fraternity: For use of the Lodges, written by the Revd. Dr. James Anderson (1680-1739 CE). Some of his inspiration he may have got from his father (see also James Anderson: Man & Mason, James Stevenson, Heredom, Volume 10, 2000, p. 94). His father, James Anderson senior (1649-1722 CE), had been a member of the Lodge of Aberdeen, where he had compiled the elaborate Mark Book ('Lockit Buik', 27 December 1670 CE) of the lodge while he was serving as its secretary, and in the 1690s he had served as its Master. The Constitutions of the Free-Masons were published in the USA by Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790 CE) in 1734 (see also The Constitutions of the Free-Masons containing the History, Charges, Regulations, & of that most Ancient and Right Worshipful Fraternity: For use of the Lodges, Anderson, Senex and Hooke, 1723 and Jean-Theophile Desaguliers. Un huguenot, philosophe et juriste, en politique, Pierre Boutin, Honoré Champion, 1999, pp. 161-165)

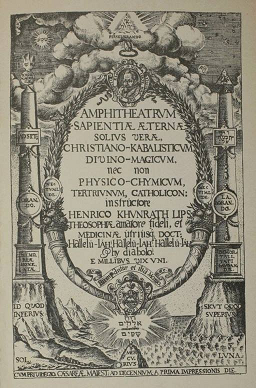

The Frontispiece to James Anderson's Constitutions (1723 edition) is full of symbolic meaning. The scene on the Frontispiece, engraved by John Pine (1690-1756 CE), depicts John Montagu, Duke of Montagu (1690-1749 CE) presenting the scroll to Philip, Duke of Wharton (1698-1731 CE), who was the next Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster. John Montagu is wearing the robes of the Order of the Garter, while presenting the Constitutional scroll and a set of compasses to Philip Wharton, dressed in his ducal robes. Both Grand Masters of the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster are surrounded by their respective Deputy Grand Master and Grand Wardens: John Beale, doctor of physic, Josias Villeneau and Thomas Morrice are to the left, with white aprons and gloves; and William Hawkins and Joshua Timson, stand next to John Theophilus Desaguliers (1683-1744 CE), dressed in clerical robes, on the far right. Both Villeneau and Desaguliers were French Huguenots, who fled France after the proclamation of the Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) by Louis XIV of France (1638-1715 CE). The Edict revoked the Edict of Nantes (1598 CE) on religious tolerance. The resulting persecution of French protestants made many of them leave France for protestant England. In the background of the scene there is a depiction of the parting of the Red Sea (Old Testament, Exodus 14:21), recalling the successful flight of the Israelites from the Egyptians to the promised land. The reference to the parting of the Red Sea might signify here the survival of a Judeo-Christian tradition that had been in danger, but was now entering a time of security. The symbolic meaning of the parting of the Red Sea is that this one event is the final act in God's delivering His people from slavery in Egypt. The exodus from Egypt and the parting of the Red Sea is the single greatest act of salvation in the Old Testament, and it is continually recalled to represent God's saving power. In Christianity the passing through the Red Sea is also symbolic of the believer's identification with the death, burial and resurrection of Christ (Paul, 1 Corinthians 10:1-4 and Romans 6:4). The pillars on both sides depict the five noble orders of architecture introduced to England by Inigo Jones (1573-1652 CE), namely the Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite. The frontispiece shows a pavement or arcade with the Five Orders, coupled, on each side; the Composite Order (first) in the foreground, receding to the Tuscan (fifth) in the background. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (ca. 80-70 BCE, died after ca. 15 BCE) mentioned the five noble orders of architecture in his work de Architectura. Three of the Classic Orders, the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian, were used by the Greeks. The Romans adopted these three and added the Tuscan and the Composite, so making the Five Orders of Architecture. The five pillars may also allude to the monarchs who supported the rebuilding of St Paul's Cathedral by Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723 CE) between 1675 and 1708 CE. The five monarchs were: Charles I of England (1600-1649 CE, ruled 1625-1649 CE), Charles II of England (1630-1685 CE, ruled 1649-1651 CE and 1660-1685 CE), James II of England (1633-1701 CE, ruled 1685-1688 CE), William III of England (1650-1702, ruled 1689-1702 CE) and Anne, Queen of Great Britain (1665-1714 CE, ruled 1702-1714 CE). In the foreground is the Greek word εuρηκα (Archimedes' famous exclamation "I have found it!") below a representation of the 47th proposition of Euclid of Alexandria or Pythagorean theorem, a symbol which is traditionally associated with Past Masters in freemasonry. James Anderson in his Constitutions (1723 CE) wrote about the 47th proposition: “The Great Pythagoras, provided the Author of the 47th Proposition of Euclid's first Book, which, if duly observed, is the Foundation of all Masonry, sacred, civil, and military…. This wise philosopher, Pythagoras, enriched his mind abundantly in a general knowledge of things, and more especially in Geometry, or Masonry. On this subject he drew out many problems and theorems, and, among the most distinguished, he erected this, when, in the joy of his heart, he exclaimed Eureka, in the Greek language signifying, "I have found it," and upon the discovery of which he is said to have sacrificed a hecatomb. It teaches Masons to be general lovers of the arts and sciences.” The Pythagorean theorem and the love of the arts and sciences can be traced back to ancient Greece. Geometry is about measuring and creating standards, understanding and reasoning (philosophy). Plato made a study of geometry or some exact science an indispensable preliminary to that of philosophy. The story goes that, in order to emphasize the importance of geometry, placed above the entrance to the Platonic school of philosophy (the Academy) were the words: "Μηδείς άγεωμέτρητος είσίτω μον τήν στέγην" (Let no one ignorant of geometry enter my doors) (Smith, 1951, p. 88; Katz, 1993, p. 48). According to Plutarchus, Plato also wrote about God as the great Geometer: "Άεί θεός γεωμετρεΐ" (God eternally geometrizes) (Plutarchus, 1841, viii; Kline, 1964, p.78). We also read about the divine nature of "number and weight" in the Wisdom of Solomon (11:20): “Even apart from these, men could fall at a single breath when pursued by justice and scattered by the breath of thy power. But thou hast arranged all things by measure and number and weight.” (see also The Foundations of Modern Freemasonry: The Grand Architects: Political Change and the Scientific Enlightenment, 1714-1740, Ric Berman, Sussex Academic Press, 2012, p. 136 and Huguenot Heritage: The History and Contribution of the Huguenots in Britain, Robin D. Gwynn, Sussex Academic Press, 2001, p. 116 and The Regular Architect, Or, The General Rule of the Five Orders of Architecture by Giacomo Barozzio Da Vignola, John Leeke (transl.), D. Newman, 1682 and Canon of the Five Orders of Architecture, Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola, Courier Corporation, 2013 and The Merging of Two Worlds: The Convergence of Scientific and Religious Thought, Roy E. Bourque, WestBow Press, 2011, p. 147-148 and History Of Mathematics Vol I, David Eugene Smith, Dover Publications Inc., 1951 and A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, Victor J. Katz, Harper Collins, 1993 and Convivalium Disputationum libri novem, viii, Plutarchus, Didot, 2 ed., 1841 and Mathematics in Western Culture, Morris Kline, Oxford University Press, 1964).

With regard to the ethical meaning of the 47th proposition of Euclid there is the Ethica ordine geometrico demonstrata (1677 CE) of Benedictus de Spinoza (1632-1677 CE). The Ethica was written in the same format as Euclid's Στοιχεῖα as an axiomatic system. It was a moral philosophy based on the logical format of the Στοιχεῖα which is 'more geometrico' (Bennett, 1984, p. 16-17). In his Ethica, Spinoza described a journey whereby the mind embarks on an exodus from a state of bondage to false beliefs and systems of power to the promised land of clarity and self-knowledge, which culminated in his 47th proposition. In 'Pars II, Propositio XLVII' Spinoza stated: "Mens humana adaequatam habet cognitionem aeternae et infinitae essentiae Dei" (II, P47). This adequate knowledge of the essence of God serves as a means to achieve a 'third kind of knowledge' (II,P40,S2). For Spinoza the 'first kind of knowledge', was when someone saw things as contingent, happening by chance. The use of reason allowed man to enter the 'second kind of knowledge', when he perceives things as necessary and eternal (V,P28). Finally the 'third kind of knowledge', which is intuition, deals with one's essence as modes of God in a state of pure perenity, eternity (Greenberg, 2007, p. 343; de Castela). The third kind of knowledge is an immediate understanding (intuition) of one's self and one's place within the universe or one's place within God. Spinoza also dealt with the virtues required for social and political life, chief among these being friendship and the responsibility for each man to consider the needs of society (R.A. Graeter, 2011; S.B. Smith, 2003). This goes back to the Greek and Roman idea of civil duty towards society. With regard to one's civil duty, Cicero had written: "non nobis solum nati sumus ortusque nostri partem patria vindicat, partem amici" De Officiis (1:22) (see also Freemasonry's System of Morality, What makes it so peculiar and why do we hide it?, Richard A. Graeter, Caliburn Lodge, 2011 and Spinoza's Book of Life: Freedom and Redemption in the Ethics, Steven B. Smith, Yale University Press, 2003 and Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions, Volume 1, Yudit Kornberg Greenberg, ABC-CLIO, 2007 and The three kinds of knowledge, Leon de Castela and A Study of Spinoza's 'Ethics', Jonathan Bennett, CUP Archive, 1984).

The charioteer in the sky which is depicted in the Frontispiece is an Indo-European symbol for the Sun God and also a symbol for the mystical ascent of the soul. A "sun chariot" is a mythological representation of the sun riding in a chariot. The concept is younger than that of the Egyptian solar barge, and typically Indo-European, corresponding with the Indo-European expansion after the invention of the chariot in the 2nd millennium BCE. In the sky directly overhead the sun approaching its meridian height is allegorized in the figure of Apollo Helios, Greek God of the Sun. The image of the Sun also refers to the Analogy of the Sun in the Platonic system of philosophy, where Socrates compares the "Good" with the sun (The Republic VI, 507b-509c). The Roman deity Sol Invictus was also depicted riding a quadriga. The Vedic Sun God Surya is also depicted riding a chariot drawn by seven horses. Interestingly Krishna is the guide and charioteer of Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita, which is part of the Hindu epic Mahabharata. In Chinese mythology the Lotus Tree of Life, the Celestial Horse from ancient China, traditionally is seen pulling the Chariot of the Emperor Archer Sun-God. The warhorses (cerigyn nojan) of the Mongols were called "Celestial Horses" by the Chinese. The chariot also refers to the charioteer as a symbol for mystical ascent of the soul. The Eleatic monist Parmenides (early 5th century BCE) in his poem On Nature refers to a visionary chariot ride up through the gates of night and day. Pindar (ca. 522-ca. 443 BCE) in his First Olympian Ode also refers to a golden chariot given by the gods: "Honoring him, the god gave him a golden chariot, and horses with untiring wings". Socrates (469-399 BCE) refers to the chariot as the aeterial vehicle of the soul in Plato's (424/423-348/347 BCE) Phaedrus. The soul is portrayed as a charioteer (Reason), and two winged steeds: one white ('spiritedness', the irascible, boldness;) and one black (concupiscence, the appetitive, desire). The Neoplatonists Plotinus (204/5-270 CE) and Iamblichus (ca. 245-ca. 325 CE) refer to the soul's struggle to ascend as a unified being to the vision of immutable reality. In the Old Testament we also find references to chariots in Kings 2:11-12 where a chariot takes the prophet Elijah up to the heavens in a whirlwind and the four-wheeled chariot of the Cherubim in Ezek 1:15-25and 10:8-22. Christians adopted the image of the Sun (Helios or Sol Invictus) to represent Christ. In this portrayal he is a beardless figure with a flowing cloak in a chariot drawn by four white horses, as in the mosaic in Mausoleum M or 'Tomb of the Julii', discovered under Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome. In the book Revelation 6:2-8 and 19:11 of John on the opening of the seven seals the rider on the white horse is called "faithful and true". The references to Archimedes, Pythagoras and Plato in the Frontispiece put freemasonry within the anti-Aristotelian tradition. The overall impression of the frontispiece is one of great triumph on many levels: the philosophical and scientific, organisational and traditional, and the spiritual and transcendent. These various elements combine to present Anderson's view of history as the careful unfolding of a divine plan (see also Phaedrus, Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9, Plato, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925, 253c-254e and Pindar's First Olympian Ode, Pindar, 86-87 and Marsilio Ficino and the Phaedrian Charioteer Ed. and trans. Michael J. B. Allen, Publications of the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, UCLA, no. 14. Univ. of California Press, 1981, p. 3-4 and Die Mosaiken der Juliergruft im Vatikan, Othmar Perler, 1953, Universitätsverlag, 1953, p. 34-36, Theurgy in Late Antiquity: The Invention of a Ritual Tradition, Ilinca Tanaseanu-Döbler, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2013, p. 214 and God's Steed- Key to World Peace, Daryl Breese, Gerald D'Aoust, Lulu.com, 2011, p. 55 and Chinese and Indo-Europeans, E.G. Pulleyblank, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1966, p. 9-39).

The key 'constitutional' features of the Constitutions were the reworked Charges and Regulations. The Charges occupy seven pages (pp. 49-56); and the Regulations, compiled by Payne, fourteen pages (pp. 58-72). The new Constitutions put forward an 'ethos of education and religious tolerance'. In addition Anderson compiled an artificial history (faux history) which was designed to set a literary context for Freemasonry. The constitution supported the state and its legitimate authority and, at the same time, encouraged, if not demanded, religious tolerance and moral integrity. Freemasonry was designed to be above political and social censure, admitting only 'good and true Men, free-born, and of mature and discreet Age, no Bondmen, no Women, no immoral or scandalous men, but of good Report'. Bondman refers to the Hebrew word עֶבֶד (ebhedh) for slave in the Torah, either foreign (Genesis 43:18; 44:9,33; Leviticus 25:44,46) or Hebrew (Leviticus 25:42; 2 Kings 4:1). In the New Testament (Revelation 6:15) it is used as a translation of δοῦλος, meaning someone who belongs to another (bond-slave) in contrast with a freeman. The Hanoverian freemasons created a new structure which combined latitudinarian religious tolerance with support for the parliamentary establishment (Whigs), sociability and entertainment, and the quest for and disbursement of scientific and general knowledge (Newtonianism): ideas that can be considered to be at the core of the English Enlightenment. For the new freemasons Newton's theories demonstrated not only scientific and physical truths, but also revealed a deeper moral truth. In Newtonianism a new connection developed between religion, science and morality. Newton came to be the leader of the so-called 'scientific revolution' and had spent a great deal of his 'time and energy using his mathematical , physical, and celestial theories to uncover patterns of Biblical revelation'. Freemasonry was being rebuilt in part on the intellectual foundations of freedom of the person, property and constitutional government: themes that were embraced and reinforced by the Whig aristocrats, magistracy and learned professionals at the helm of the new Grand Lodge (see also The Foundations of Modern Freemasonry: The Grand Architects: Political Change and the Scientific Enlightenment, 1714-1740, Ric Berman, Sussex Academic Press, 2012, Chapter three and The Constitutions of the Free-Masons containing the History, Charges, Regulations, & of that most Ancient and Right Worshipful Fraternity: For use of the Lodges, Anderson, Senex and Hooke, 1723 and Efflorescences and economic growth in world history: rethinking the"Rise of the West" and the Industrial Revolution, J. Goldstone, University of Californa, Davis, 2002, p. 372).

The new Constitutions of the Free-Masons (1723 CE) was based on the concept of a natural religion read from the Book of Nature, apprehended by human reason and binding all men who rejected stupid atheists and irreligious Libertines: "A Mason is oblig'd, by his Tenure, to obey the moral Law; and if he rightly understands the Art, he will never be a stupid Atheist, nor an irregular Libertine." The main elements in the opening of the constitution are the moral law, the art, stupid atheism and irregular libertinism. The Moral Law refers to moral absolutism, the ethical view that particular actions are intrinsically right or wrong. Moral absolutism teaches that there are universal moral principles by which all actions are to be judged. It is the duty of a freemason to learn the universal moral principles and to act accordingly. One example of a universal moral principle is the golden rule or regula aurea (law of reciprocity), the principle of treating others as one would wish to be treated. The art may refer to the ancient Greek τέχνη (technê), which is translated as either craft or art (see Epistēmē and Technê). Technê is related to ἐπιστήμη (epistēmē) in the implication of knowledge of principles, but in addition technê means practice. We could relate understanding of the moral law to ἐπιστήμη and τέχνη to an art or craft. Freemasonry deals with the ἄσκησις (training or exercise) in order to develop the morality of the freemason and mastering the λόγοι (principles) behind the art and developing into a τεχνίτης (artificer, craftsman, master mason). Being a freemason is a matter of moral practice rather than just words (έργα ού λόγοι) (see also Moral Theory: An Introduction, Mark Timmons, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2012, p. 91 and The Art of Living: The Stoics on the Nature and Function of Philosophy, John Sellars, Routledge, 2011, p. 20, 25 and 27 and The Freemasons: What They Are, what They Do, what They are Aiming at, Louis Gaston de Ségur, P. Donahoe, 1869, p. 90)